Jan 17th, 2023 - Category: Change

A company simply called Arm might be the smallest, least known company with the largest influence on microprocessors ever. It began with humble beginnings 35 years ago creating a CPU for their own computer. Since then it has ridden out storm after storm in the turbulent semiconductor industry to eventually compete with Intel and be at the core of some of the most popular devices in history. The entire story is told in an incredibly interesting and detailed three part article in ArsTechnica (1, 2, 3). Part 1 starts with a very readable primer on CPUs focusing on Arm’s breakthrough idea of RISC - Reduced Instruction Set Computing (as opposed to Intel’s CISC - Complex Instruction Set Computing). Part 2 details their rise to fame in the exploding mobile device market of the early 2000s. And Part 3 brings the story to modern times explaining breakthroughs such as the fact that the processor in the original iPod, based on Arm’s designs, eventually led to modern CPUs that have surpassed the power of Intel’s best offerings while using only a fraction of the electricity. Now almost all of Apple’s desktops, laptops, phones, and tablets are using this same underlying technology for their microprocessors and it all started with Arm.

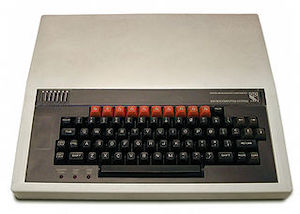

It doesn’t look like much, but this was the first computer to use an Arm chip, the Acorn Archimedes, and the article summarizes Arm’s history beautifully in one paragraph:

It doesn’t look like much, but this was the first computer to use an Arm chip, the Acorn Archimedes, and the article summarizes Arm’s history beautifully in one paragraph:

After 35 years, ARM had come full circle. It started in 1985 as a chip for desktop computers—in particular, the Acorn Archimedes. But when the Archimedes failed to capture the market, the ARM chip was spun out into its own company in 1990. After a slow start, ARM became the standard for the embedded CPU market and made its way into popular mobile devices like the iPod, the Game Boy Advance, and smartphones like the iPhone and Android. Now, at long last, it was back in personal computers.

But the real beauty of the article is in the author, Jeremy Reimer’s, observations about the technology sector then and now. In Part 2, he tells this brief story about the CEO of Arm at the time, Robin Saxby, showing how he stayed true to his principles even in the face of what must have seemed like a major setback.

In a meeting with his former employer Motorola, Saxby recalled the executive closing by saying, “And of course, we won’t be able to pay you any license fees or royalties.” The company expected ARM to be happy to be paid in “exposure” since Motorola could have done the job itself. Saxby asked the executive how many engineers he had working on the project. The answer was about 200. “Do you realize,” Saxby asked, “that the license fee you’d pay to us is a quarter of what you’re paying for your engineers?” He still refused to give ARM money, and Saxby walked away from the deal.

The author also highlights Saxby’s collaborative leadership principles in another quote from Part 2.

For Robin Saxby, the idea of working with rival chip companies was always part of the strategy. “Turn your enemies into friends,” he would say. “Why should they fight you if they can make more money for themselves by collaborating with you?”

And finally in Part 3, Reimer summarizes Saxby’s leadership genius.

But the key to Saxby’s management approach was simple yet uncommon in the business world: ARM grew because it helped others grow. It treated its employees more like people and less like human resources, giving them chances to learn and succeed along with the company. “I’m a great believer that in any team,” he told me, “any member is better at something than somebody else, so to get the team to perform you want everyone to perform on their best axis. Teams that work well together work better.” He emphasized the importance of being honest with employees and not overpromising what the company had to offer.

In a few thousand words ArsTechnica has not only explored the fascinating history of Arm, but also demonstrated that true success has great leadership as a critical factor. Some companies have transformative technologies, created by visionary founders, but can’t manage their business and fail. Others underachieve and die in mediocrity, but the story of Arm demonstrates that a fine balance is needed. Leadership does matter.